The U.S. Military Campaign Targeting Venezuela and Nicolás Maduro: What to Know

The U.S. military has launched a campaign that it says targets illegal drug trafficking in the Caribbean, but the reported capture of Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro has intensified scrutiny over the operation’s true aim.

U.S. President Donald Trump announced on January 3 that U.S. forces had captured Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro and his wife and flown them out of Venezuela following a “large-scale strike” against the country. U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi said that Maduro had been indicted in the United States and would face drug and weapons charges in the Southern District of New York.

Trump said during a press conference that the United States would “run” Venezuela “until such time that we can do a safe, proper, and judicious transition.” He and other senior U.S. officials did not provide further information on how Venezuela would be governed in the intervening time or how it could involve the U.S. military, but they noted their intention to develop the country’s vast oil reserves with U.S. energy companies.

Several world leaders have condemned the capture, while others called for immediate de-escalation. It is unknown how the Venezuelan regime will respond, though a few senior officials have begun to speak out publicly. Meanwhile, María Corina Machado—Venezuela’s opposition leader—said the U.S. government had fulfilled its promise to uphold the law and called for Edmundo González Urrutia, who won the last election, to be installed as president and commander-in-chief of Venezuela’s military. “Today we are prepared to enforce our mandate and take power. We will remain vigilant, active, and organized until the democratic transition is made concrete,” she said.

Experts are unsure whether the opposition can seize control of the country quickly without further backing, however.

“Maduro is gone but the repressive elements of the regime are still there and in control. It is a huge country, so it is hard to control territorially,” said Shannon K. O’Neil, CFR senior vice president and director of studies. “There are also many armed groups—military, secret police, colectivos, [National Liberation Army] militias—that democratic and U.S. friendly leaders in Venezuela would need to bring to heel. Edmundo González, who was on the ballot and won the last election, and Machado are out of the country. The United States can fly back in either or both, but it remains unclear how the opposition—which is unarmed—gains physical control of the streets, a basic prerequisite to governing.”

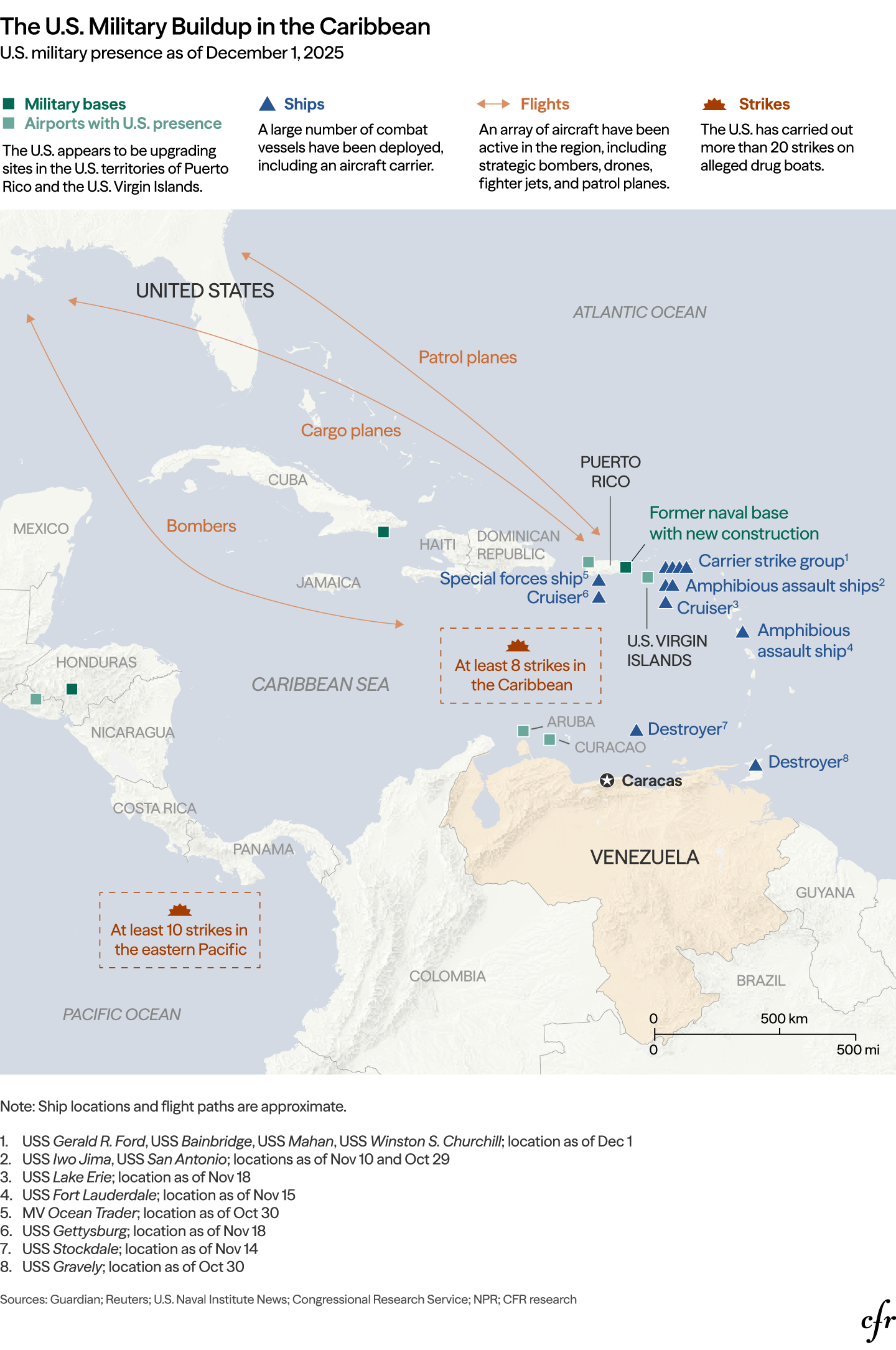

Since early September 2025, Trump has mounted an escalating pressure campaign against the Maduro regime, which U.S. officials have accused of leading a drug cartel that the State Department designated a foreign terrorist organization in November. In recent months, Washington significantly increased its air and naval presence in the region as part of Operation Southern Spear, a U.S. military campaign that it says targets drug trafficking in the Caribbean. It has authorized more than twenty lethal strikes on alleged drug trafficking boats.

The Trump administration had framed the operation as necessary to curb the flow of drugs from Latin America to the United States, but some experts said the campaign’s scope and intensity go beyond counternarcotics objectives, long raising the possibility of a broader effort to force regime change in Venezuela. Other heightened U.S. pressure on Venezuela, including a naval blockade on all sanctioned oil tankers into the country, which followed expanded sanctions against several Venezuelan oil shipping companies, had also raised concerns about escalation and broader regional instability.

What is Operation Southern Spear?

On November 13, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth announced the formal launch of Operation Southern Spear, which he said was aimed at targeting “narco-terrorist” organizations and disrupting illegal drug trafficking in the Western Hemisphere. The Pentagon described the effort as a U.S. military “counter-narco-terrorism campaign” intended to safeguard U.S. national security.

Hegseth’s announcement came shortly after the Senate voted down a bipartisan war power resolution that would have blocked the Trump administration from using military force within or against Venezuela without congressional authorization. Another vote occurred on December 17, in which the U.S. House of Representatives rejected a pair of Democrat-backed resolutions that would have reined in Trump’s military campaign toward Venezuela.

How is the operation being carried out?

Before the United States’ January 3 strike and capture of Maduro, the operation, led by U.S. Southern Command and Joint Task Force Southern Spear, involved a regional buildup of extensive air and naval assets, including bombers, drones, aircraft carriers, and amphibious assault ships. The name “Southern Spear” was first introduced by the U.S. Navy in January to describe a maritime mission that uses a hybrid fleet of vessels with robotic and autonomous systems to “increase presence in, and awareness of, strategically and economically important maritime regions.” The effort was later expanded into a broader, formal military operation that the United States said was focused on interdicting drug cartels in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific.

But when it came to the operation’s stated goals of disrupting illegal drug trafficking and dismantling “narco-terrorist” networks in the Western Hemisphere, there was “a lot of mismatch,” said Roxanna Vigil, a CFR international affairs fellow in national security, noting that the United States was using “a huge naval deployment against small, little drug boats.” More traditional law enforcement approaches, such as targeted interdictions, had historically been the standard response to maritime drug trafficking in the Caribbean.

Approximately fifteen thousand U.S. military personnel have reportedly been deployed in 2025, making it one of the largest U.S. military buildups in the region since the Cold War.

How serious is the drug trafficking threat in the Caribbean?

The Trump administration has argued that drug trafficking poses a direct national security threat warranting the use of military force. In early October, the administration notified Congress that the United States was engaged in an “armed conflict” with drug cartels, arguing that the cartels’ actions constitute “an armed attack” against the country. Now captured by U.S. forces, Maduro—along with his wife and son—faces drug trafficking charges in New York.

The government’s earlier declaration represented a sweeping assertion of war powers without prior approval from Congress and permitted the United States to use lethal force against cartel members—whom the administration considers “unlawful combatants.” (During a congressional briefing, Pentagon officials reportedly said that they don’t need to positively identify individuals on the targeted vessels as specific cartel members to carry out lethal strikes.)

The Trump administration also elevated drug trafficking as a priority in its 2025 National Security Strategy [PDF], which calls for efforts to “neutralize” and target “narco-terrorists, cartels, and other transnational criminal organizations” using lethal force.

“The administration calls the current situation a ‘non-international armed conflict,’” said Will Freeman, CFR fellow for Latin American studies. The use of that term “seems to allow arbitrary designation of combatants; certainly, near-total discretion for the president, possibly violating Article II of the Constitution.”

The Caribbean has long served as a major transit corridor for cocaine, heroin, and marijuana moving from South America to the United States and Europe. According to U.S. government estimates, about one-third of all cocaine entering the United States passes through the Caribbean, facilitated by the region’s vast, dispersed geography and limited maritime law enforcement capabilities.

Yet trafficked cocaine accounts for far fewer U.S. overdose deaths than synthetic opioids like fentanyl, virtually all of which—as well as about three-fourths of trafficked cocaine—actually comes from Mexico, Freeman said. As a result, “whatever actions are taken in the Caribbean have no effect on fentanyl,” Vanda Felbab-Brown, an expert on drugs and counternarcotics policies at the Brookings Institution, told NPR.

Is the U.S. moving toward regime change against Maduro?

The reported capture of Maduro by U.S. forces marks a dramatic escalation in Washington’s military campaign against the Venezuelan government.

Many argued that the operation’s scope and scale—including the administration’s authorization of covert CIA action in Venezuela—was a clear indication of a broader plan to oust Maduro. “If Maduro is not the legitimate leader of Venezuela and is instead a narco-terrorist and a cartel kingpin, it would be difficult to understand why the Trump administration would surround the country with a gigantic armada only to leave him in power,” CFR Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies Elliott Abrams, who served as special representative for Venezuela in the first Trump administration, wrote for Foreign Affairs.

Maduro had accused the Trump administration of “fabricating” a war and trying to take control of Venezuela’s lucrative oil resources. Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves, but decades of government mismanagement, underinvestment in the sector, corruption, and U.S. sanctions have led to a drastic decline in the country’s production and export capacity.

On January 3, Trump said that the United States planned to “run” Venezuela. He noted that U.S. companies would rebuild the country’s oil infrastructure and its oil to other countries.

In addition to economic action, including new sanctions on shipping companies and seizing two oil tankers, Trump had seemingly applied direct diplomatic pressure, reportedly pressing Maduro to step down in a November 21 call.

How did other governments respond to the United States’ military buildup?

The region’s response were mixed. Several U.S. partners, including El Salvador and the Dominican Republic, expressed support for U.S. operations, with some allowing U.S. forces access to their bases and airports. The U.S. military has also increased its presence in its Caribbean territories, reopening the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station in Puerto Rico and deploying additional forces to the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Other governments were more critical. On November 11, Colombian President Gustavo Petro announced that the country had suspended intelligence sharing efforts with the United States, while Ecuador overwhelmingly rejected President Daniel Noboa’s proposal to allow foreign military bases in the country—including a potential U.S. presence.

CFR’s Vigil said noted that Latin America is currently “quite divided,” with countries largely acting in pursuit of their own interests, so any such strikes would reveal if governments respond critically or not.

Russia had also signaled support for Venezuela, a longtime ally. After Maduro’s capture, the country called for an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council, and it condemned the U.S. action as “an act of armed aggression against Venezuela.” Russian President Vladimir Putin reportedly called Maduro a day after the December 10 tanker seizure to “reaffirm” Moscow’s support. The two countries finalized a major strategic partnership treaty in October that expands bilateral cooperation on energy, mining, defense, and counterterrorism. Both Russia and Venezuela are under extensive U.S. sanctions.

Will Merrow created the graphic for this article.